Mark’s Notebook - Page 60

This item was sent to me by Steven Hill last year, and it’s one of my favorite type/film gaffes.

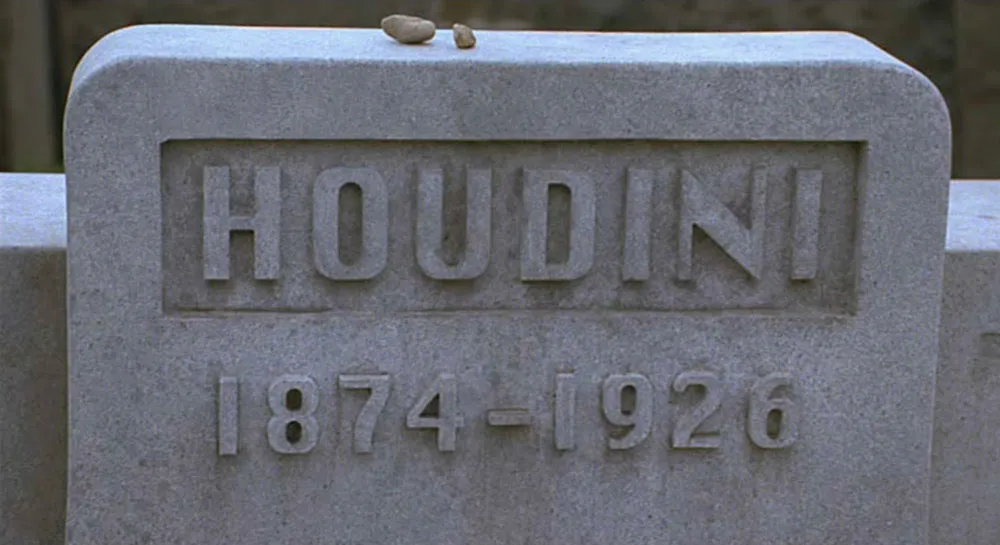

It’s from a thriller called Oxygen made and set in 1999. It stars Adrien Brody as a clever kidnapper with a Houdini fixation. In one scene, he instructs the husband of the woman he’s kidnapped to deliver the money to him at Houdini’s grave and there’s a close-up of the gravestone:

In case you don’t recognize it, that’s the TrueType version of the old Macintosh system font, Chicago, released in 1989.

I also think it’s funny how the numbers for the years are not carved into the marble but, instead they project outward. I don’t know much about cutting gravestones, but I would think you would waste a lot of stone to get that effect. I also wonder how those little pebbles got up there… Mysteries upon mysteries!

Update: According to Victor Caston, it’s a Jewish tradition to place pebbles on the headstone, and Houdini was Jewish. One mystery solved, anyway. Amazing yet intermittent attention to detail.

Further Update (June 25, 2005): According to reader Zaldamo, the real Houdini gravestone features raised letters. (It’s also quite a bit fancier.) I did say I don’t know much about how they make gravestones. One thing is still certain: Apple’s Chicago font didn’t exist in 1926.

This one was news to me: Jean François Porchez, proprietor of Porchez Typefoundrie in France, has a personal weblog called Chez Porchez. He also has a hand in the French type blog Le Typographe.com.

Berlin-based Erik Spiekermann, designer of the ubiquitous Meta, has one called spiekerblog. According to a recent interview on typeradio, he created it so he wouldn’t have to answer so many emails asking the same questions over and over.

Finally, one of the first weblogs I ever knew about was Grant Hutchinson’s splorp blog. As a type designer, he was responsible for a large portion of the old Image Club type library. Image Club is no longer around, but, after several changes of hands, many of their fonts still are available through Agfa Monotype, including his ever-popular Fajita. Grant is now at Veer in Calgary, Alberta, which he helped start up with his Image Club cohorts. [Update: Veer no longer exists, so I removed the link.]

Lettering on the cover of a vintage travel guide. Seen in an antique store in Frazee, Minnesota in 2003. I really like the “r” a lot.

When I wrote Typecasting: The Use (and Misuse) of Period Typography in Movies over two years ago, I closed it with:

“I hope to add more examples in a follow-up article. If you have any film/type gaffes to share, drop me a line.”

Well, lots of you did drop me a line, but so far I have not written the follow-up article. Instead, I have decided to post examples here, filed under “Son of Typecasting.”

Not long after writing and posting Typecasting in December 2001, I learned from a reader that a similar article by Scott Stowell had been published earlier that year in Trace/AIGA Journal of Design, Vol. 1, No. 1, called “Accident Grotesk.” I sent for a back issue to check it out.

Had I seen it before I wrote my article, I might have had second thoughts. The premise — and even the tone — was similar. However, Stowell chose completely different examples: Titanic (1997), Topsy-Turvy (1999), Amistad (1997), Donnie Brasco (1997), Dazed and Confused (1993), The Perfect Storm (2000), and American Psycho (2000).

After reading it, I generally thought it was good, but I was a bit disappointed. In a few of the examples Stowell gives, I think the fonts are mis-identified. For example, he claims that the lettering on the gangway shown early in Titanic is set in ITC Officina (1990-1998):

For one thing, the capital “I” in Officina has serifs. Other than that, it’s very close, but I don’t think it quite matches. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to identify what it is, if it’s not Officina. I do agree that it does not look right for the era, whatever it is.

When I wrote my article, I wanted very badly to find type gaffes in Titanic but came up emptyhanded. After seeing Stowell’s find, I took another look and found an even better example:

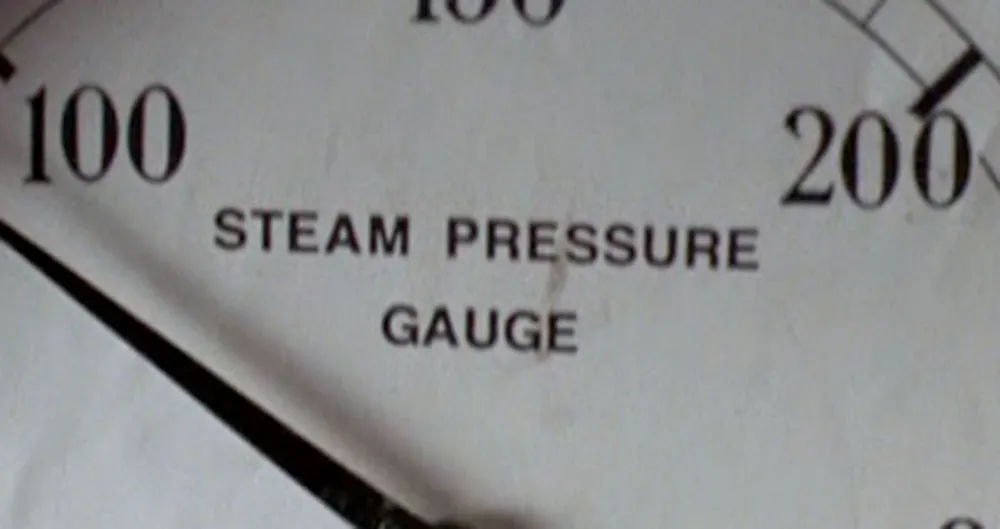

The steam pressure gauge label is set in Helvetica (1959).

(On a non-type-related note, there are also the famous Picasso and Braque paintings shown in one scene, but maybe they made it to the life boats.)

Anyway, I don’t want this to be a blow-by-blow critique of Stowell’s article. After all, it preceded mine by nearly a year, and I must give him credit for that.

Update: Just heard from Scott Stowell, the author of “Accident Grotesk.” He maintains that it really is Officina, with the serifs on the “I” lopped off. Given that I am unable to offer a more convincing alternative, I admit that it’s possible he’s right.

Scott also tells me that, ironically, it was the steam gauge gaffe that lead to his writing the article. When designer Michael Bierut mentioned it to him in 1998, it became the genesis of his article. He left it out because he didn’t want to take credit for it and thought the use of Officina was worse anyway.

Further Update: James Mosley, who writes about the history of type among other things, points out that Helvetica is not a completely anachronistic choice for the steam gauge. There did exist at the time of the Titanic ancestors of Helvetica that looked remarkably like it in some respects. So, technically, it’s not correct for the period—I think Akzidenz Grotesk would have been a better choice—but it’s not dissimilar to what might have been used.

I recently noticed Coquette used extensively in the book “Everything for Baby” by Adélaïdé D’Andigné and Alain Gelberger, published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang last year. Notice how the baby in the photo seems very interested in the font. Obviously, a budding typophile.