Mark’s Notebook - Page 43

In my Typecasting article and Son of Typecasting here in the Notebook section, I hold films under the spotlight and (sometimes) make fun of their use of type. But what about the dedicated few who go that extra mile to create historically accurate typographic props—books, tickets, posters, newspapers, drivers’ licenses, legal documents, and so on—for movies?

Shortly after posting Typecasting on my website a few years ago, I heard from Andrew Leman (www.ahleman.com) who has made a career of forging printed ephemera for movies. He also makes and sells digital fonts based on historical references, many of which were created for use in props. Although it’s not exactly a movie prop, I really love his ElectriClerk which looks like something out of Brazil, and it actually works.

My friend David Steinlicht recently brought to my attention the work of Ross MacDonald (ross-macdonald.com). I’ve known of his work as an illustrator for years, but I had no idea he made props. Turns out, Ross is a letterpress aficionado and actually prints and binds some of his props using traditional printing and bookmaking techniques. Aging is one of his tricks and it’s shocking to read how he abuses some of his beautiful creations to make them look convincingly old and worn.

I don’t know what’s in this building, but I like the 1970s-style script lettering on their sign. Those ones look like dancing scimitars. Photographed on April 1, 2005 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

I’ve never designed a tattoo before, and not many ambigrams, either.

An ambigram is a form of lettering in which a word or phrase can be read in more than one direction. Or it may be two words combined into one image in which only one can be seen at a time, depending on how you look at it. The master of this art is John Langdon whose 1992 book Wordplay showcased his work. (A new edition is in the works.)

The design above was for a tattoo and was commissioned by a client in Canada. It reads the same if you rotate it 180°. (I don’t know where she had it placed, but she promised to send a photo.)

Ambigrams are partly luck, partly skill. I feel lucky it turned out as well as it did. I hate to think of someone permanently dyeing their skin with a design that didn’t quite work.

My sharp-eyed daughter noticed this when we were doing our yearly apple-picking this morning. Photographed at Afton Apple Orchard, Afton, Minnesota, October 9, 2005.

One of the first prominent uses of my recently released Proxima Nova is at Joyent.com where it is part of their corporate identity. Notice they are using the alternate lowercase a.

(Thanks to Stephen Coles for telling me about this.)

I’ve always had a rather vague grasp on the history of New York City. So, before taking a trip there this last summer, I rented Gangs of New York (Miramax, 2002), hoping to learn some of it. I realize the film is not perfectly historically accurate, but I really enjoyed watching it. Scorsese did a wonderful job with the story, the characters, and the setting, making me feel like I had stepped into New York City of the 1860s. However, as I’ve come to expect with Hollywood movies, the typography was a bit off base.

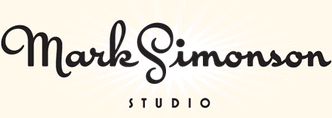

For the most part, the type choices in Gangs of New York are plausible in terms of general feel. In many cases, common 19th century wood type designs are used, especially on posters, appropriately enough, though some of these look a bit too distressed, as if they were enlarged from microfilm copies or something. Most of the signs on buildings were right on the money. I thought this one was pretty good:

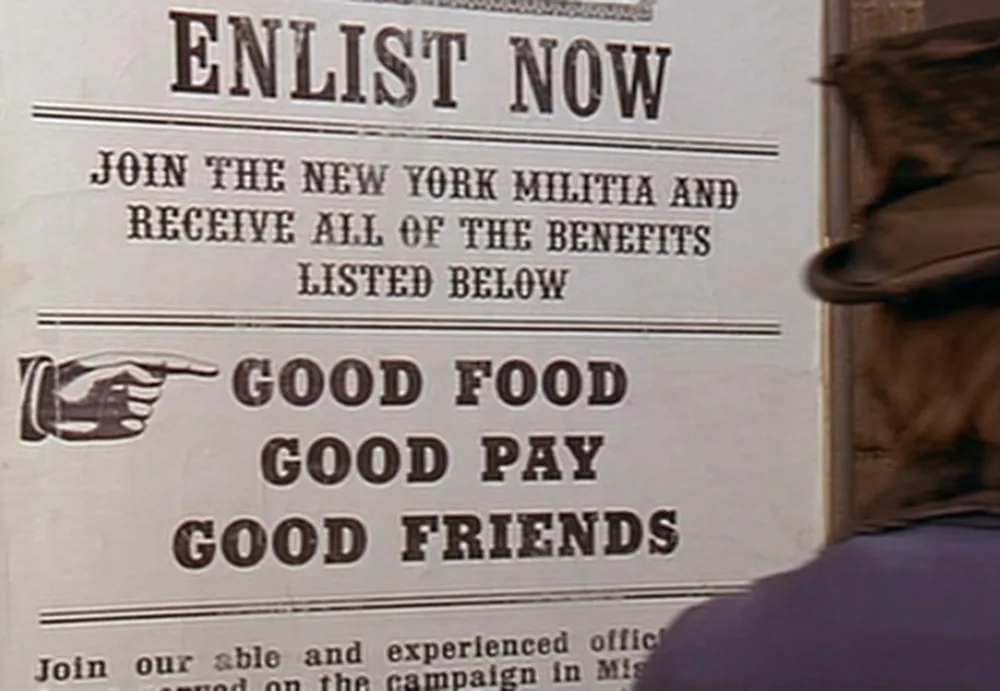

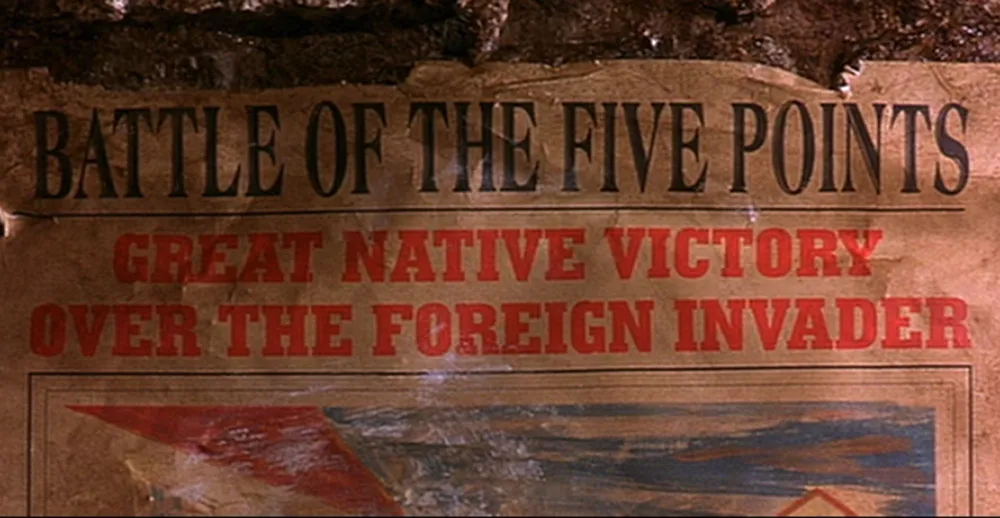

On the other hand, the movie is riddled with anachronistic type choices. Here are some examples from posters:

Here we see Bernhard Antique (1937) with two overly-distressed-looking 19th century wood types. Notice the straight apostrophe in the bottom line. Straight apostrophes and quote marks did not exist in typefaces until the advent of digital type in the 1980s. It’s a computer thing, not a typographic thing.

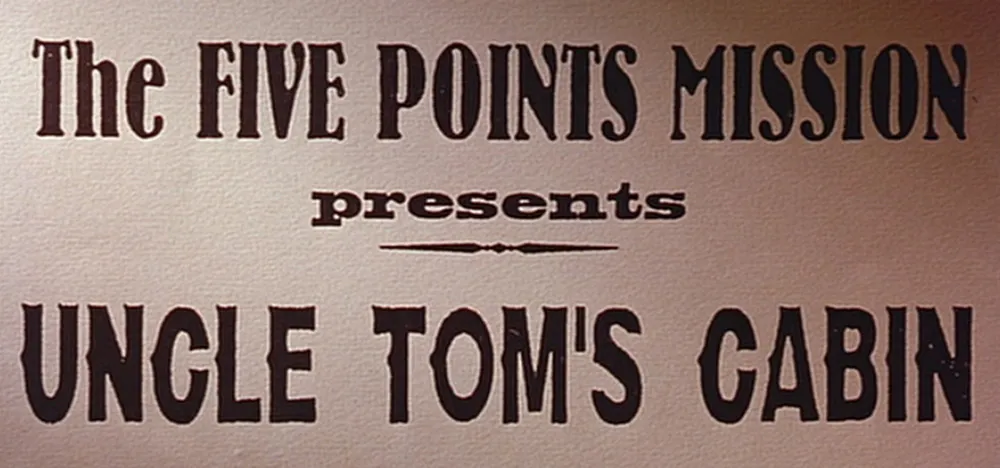

More wood type, but the second line (“Harry Watkins”) is set in Aachen (1969).

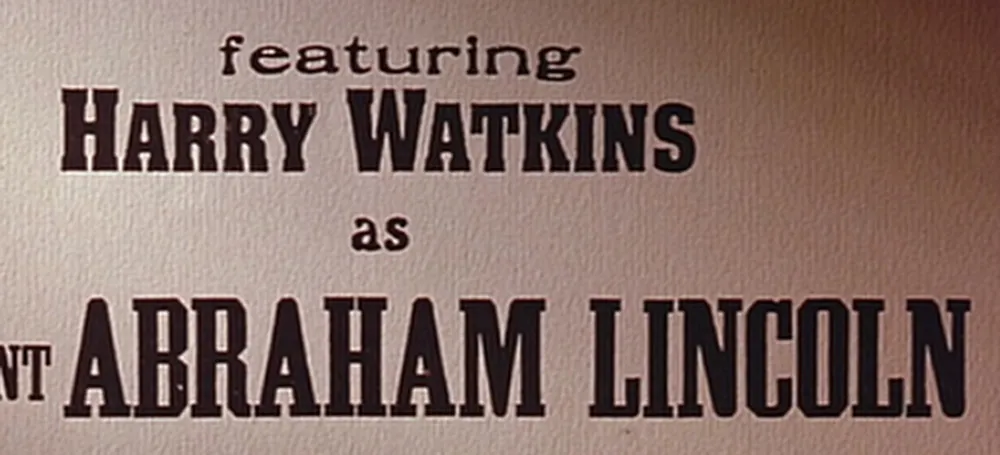

This one is set in URW Egyptienne (1950s) and ITC Benguiat (1977). Benguiat is a particularly poor choice since it is based on the Art Nouveau style of around 1900. Benguiat shows up on a couple more posters in the movie.

This is better, but not 100% historically correct. The bold font next to the pointing finger is Rockwell (1930s).

Here we have some artificially condensed Americana (1967) with Memphis (1930s). You couldn’t distort type by condensing it like this back then. It was made of wood or metal, after all.

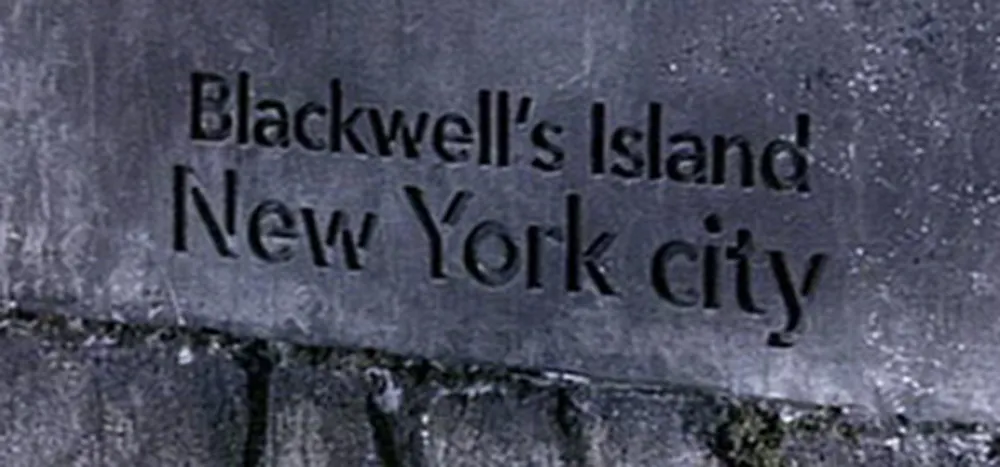

Now this is interesting. Avenir (1988) carved in marble. Few typefaces say “1860s” less than Avenir, which means “future” in French. It would actually be quite an evocative choice for a film set in the early 2000s. It’s very popular these days.

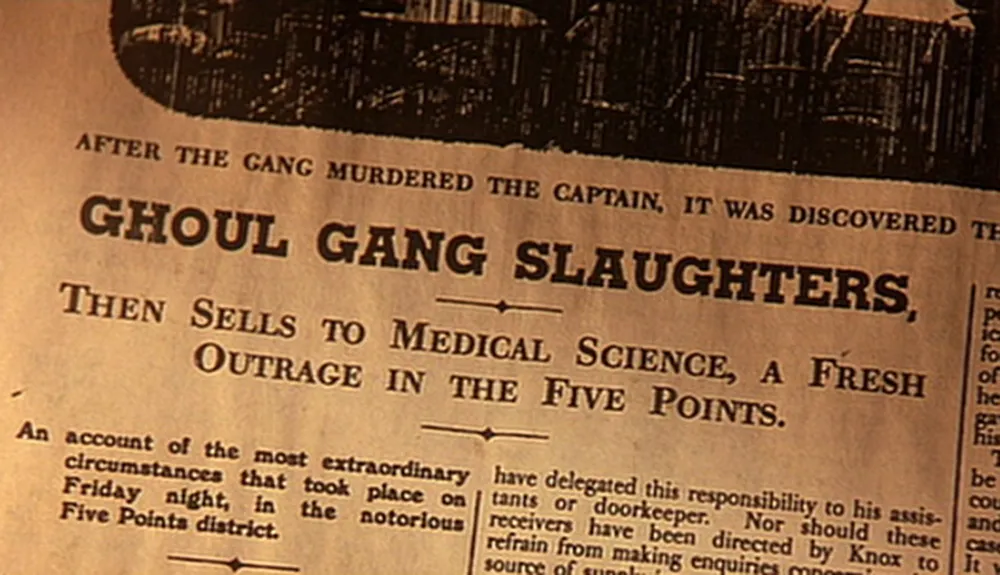

On to the printed ephemera, starting with newspapers:

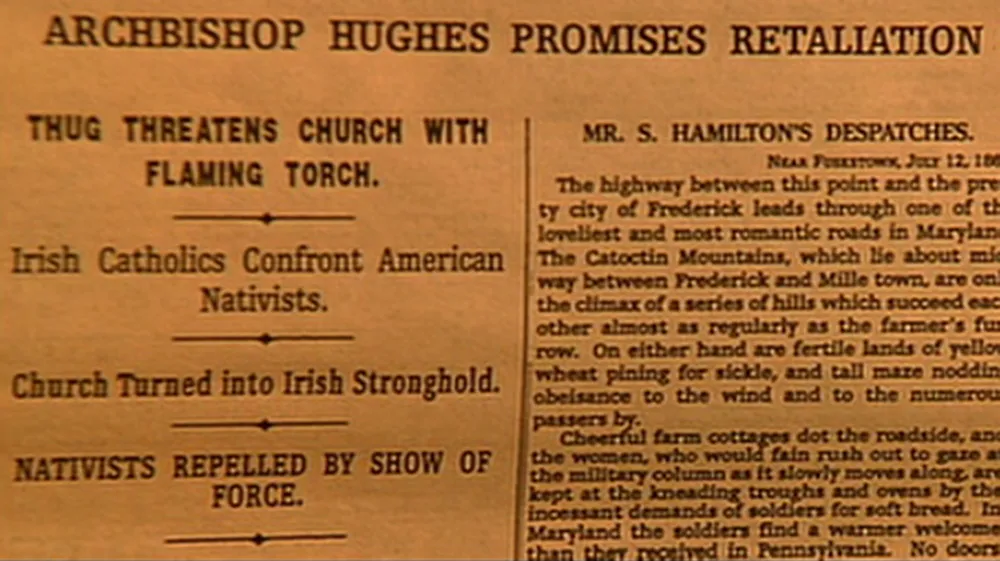

Good old (actually not so old) Memphis, again, paired with Caledonia (1940). I should point out that the way they set the type here looks right; it’s just the font choices that are wrong. There were typefaces back then that looked generally similar to these to the untrained eye, but not exactly like these. (9/5/13 Update: Eagle-eyed reader Anton Sherwood also spots Windsor (1905) in the small bold text on the left.)

The same comments go for this one. The sans serif is Helvetica (1957) and the serif font is Egyptienne (1956).

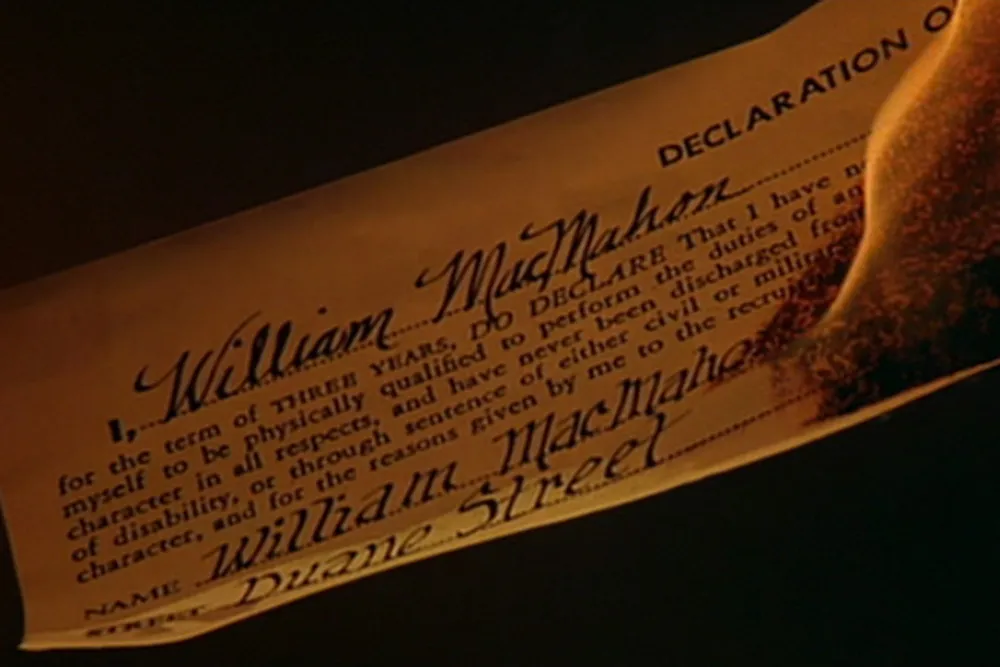

This one I love. It’s a civil war draft registration ticket. The heading is set in Futura (1927) and the text is set in Garamond (c. 1920). Now, you might say Garamond should be okay because the original Garamond types were from the 1500s, which predates the 1860s. The fact is, they were only used in the 1500s and similar types were not seen again until they were revived around 1920. I’m not sure about that handwriting at the bottom, either.

So. A great movie, but a bit flawed in the typographic department. Three out of five stars for use of type.