Mark’s Notebook - Page 43

I was very happy to be included in a short article in today’s New York Times Good Film, Shame About the Helvetica about designers who notice anachronistic font choices in films, but I was a bit taken aback when I received an email first thing this morning from the art director of Good Night, And Good Luck. She pointed out that Helvetica was not used in the film, contrary to what was claimed in the article. She said, rather, that the sign shown in the example frame was set in Akzidenz Grotesk, a face which predated (and in fact was the basis for) Helvetica, and that this choice was based on extensive research of CBS’s graphic design during the period depicted in the film.

This is no skin off my nose since I have not made any comments (yet) about the use of type in Good Night, And Good Luck. The comment was made by graphic designer and fellow font flub finder Michael Bierut, who, along with Scott Stowell and myself, is quoted in the article. Judging from the still shown in the article, I might have come to the same conclusion. As it happens, I missed the film when it was in theaters and will have to wait for the DVD release to see for myself.

If what she says is true (and she was very adamant about it), it is very unfortunate that Good Night, And Good Luck was chosen as the lead example in the article. Especially since its art director appears to be one of the rare people working in film who cares about getting the type details right.

Update: Thanks to some detective work by Stephen Coles, as reported at The Design Observer and Typophile.com, it has been confirmed that Good Night, And Good Luck really does use Akzidenz Grotesk.

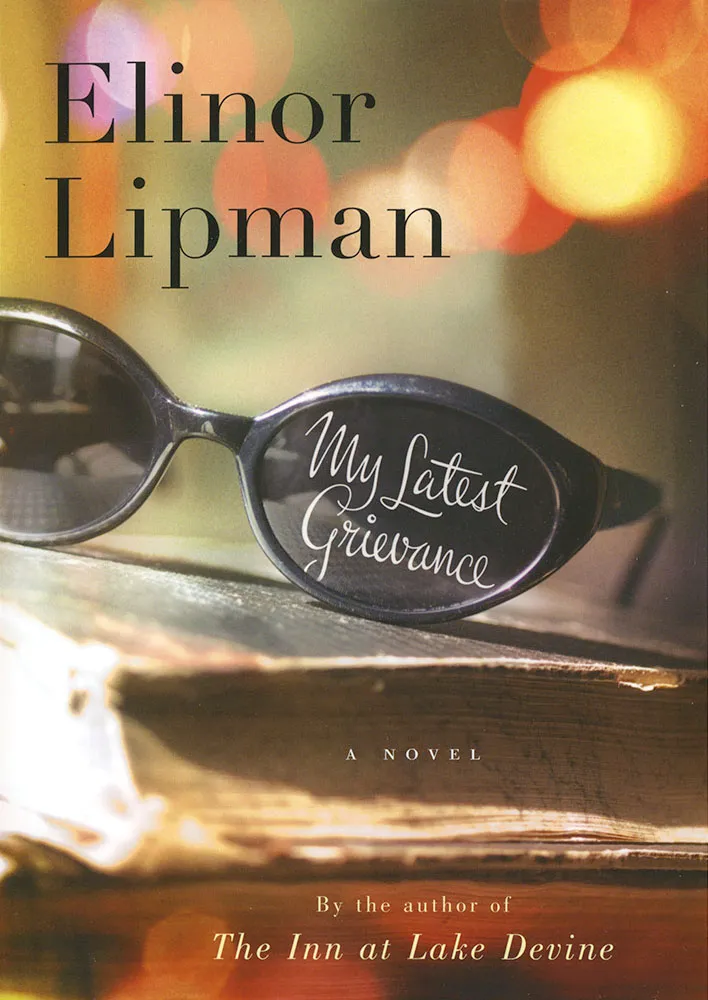

One of my recent lettering jobs was this one for the cover of Elinor Lipman’s new book My Latest Grievance, due out next spring. Houghton Mifflin art director Martha Kennedy wanted something spirited with a handwriting feel. I’m happy with the way it turned out. I’m always a little surprised that I can do this style at all. My actual handwriting is pretty erratic. I know people who can write like this. There must be something about the way their hands work that I just don’t have. Luckily, if I know how I want it to look and take my time, with a little assist from computer technology, I can pull it off. I take heart in the fact that the great lettering artists of the past would have been lost without their photostat cameras and razor blades. These things are never as easy as they look.

In my Typecasting article and Son of Typecasting here in the Notebook section, I hold films under the spotlight and (sometimes) make fun of their use of type. But what about the dedicated few who go that extra mile to create historically accurate typographic props—books, tickets, posters, newspapers, drivers’ licenses, legal documents, and so on—for movies?

Shortly after posting Typecasting on my website a few years ago, I heard from Andrew Leman (www.ahleman.com) who has made a career of forging printed ephemera for movies. He also makes and sells digital fonts based on historical references, many of which were created for use in props. Although it’s not exactly a movie prop, I really love his ElectriClerk which looks like something out of Brazil, and it actually works.

My friend David Steinlicht recently brought to my attention the work of Ross MacDonald (ross-macdonald.com). I’ve known of his work as an illustrator for years, but I had no idea he made props. Turns out, Ross is a letterpress aficionado and actually prints and binds some of his props using traditional printing and bookmaking techniques. Aging is one of his tricks and it’s shocking to read how he abuses some of his beautiful creations to make them look convincingly old and worn.

I don’t know what’s in this building, but I like the 1970s-style script lettering on their sign. Those ones look like dancing scimitars. Photographed on April 1, 2005 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

I’ve never designed a tattoo before, and not many ambigrams, either.

An ambigram is a form of lettering in which a word or phrase can be read in more than one direction. Or it may be two words combined into one image in which only one can be seen at a time, depending on how you look at it. The master of this art is John Langdon whose 1992 book Wordplay showcased his work. (A new edition is in the works.)

The design above was for a tattoo and was commissioned by a client in Canada. It reads the same if you rotate it 180°. (I don’t know where she had it placed, but she promised to send a photo.)

Ambigrams are partly luck, partly skill. I feel lucky it turned out as well as it did. I hate to think of someone permanently dyeing their skin with a design that didn’t quite work.

My sharp-eyed daughter noticed this when we were doing our yearly apple-picking this morning. Photographed at Afton Apple Orchard, Afton, Minnesota, October 9, 2005.