Mark’s Notebook - Page 11

The Artist won this year’s Oscar for Best Picture about a week ago. It seems to say something about the state of movies today that a black and white, silent picture—not even wide screen—wins the big prize. I’ve seen it, and it’s good, but I confess that I had to force myself to ignore most of the type in it in order to enjoy it.

The Artist mimics the look and feel of a late 1920s silent film. The sets, the costumes, the makeup, the lighting, the camera work, the acting—even the way it’s written—makes you almost believe you are watching a classic of the silent era. Of course, you know it’s not. After all, there are recognizable modern actors in it, like John Goodman and James Cromwell. And, for me, there was the type.

Most of the fonts they used looked more or less right for the 1920s, although quite a few were badly made free fonts (or badly made commercial fonts—those exist, too). Others are not quite from the era or were applied in an anachronistic way—for example, using negative line spacing, which is impractical to do with metal type.

But the real problem was that they used type at all. Except for things like newspapers, a few other small props, and the intertitles (more on these later), type would not have been used. Movie posters, signs, magazine covers, movie titles and credits—back in the 1920s and 1930s, that kind of thing was almost always lettered by hand. Type—and it would have been metal type, back then—was not up to the job. There were too few styles, too few sizes. It just wasn’t as flexible as someone skilled with a brush. Things that are so easy for us to do with type today were practically impossible back then, which provided plenty of work for letterers.

If you’re careful, it is possible to get close to the look of lettering with modern fonts. Some are even made to look that way (I’ve made a few myself). But for all the attention they paid to other period details, there is something slap-dash about the way this stuff was handled in The Artist.

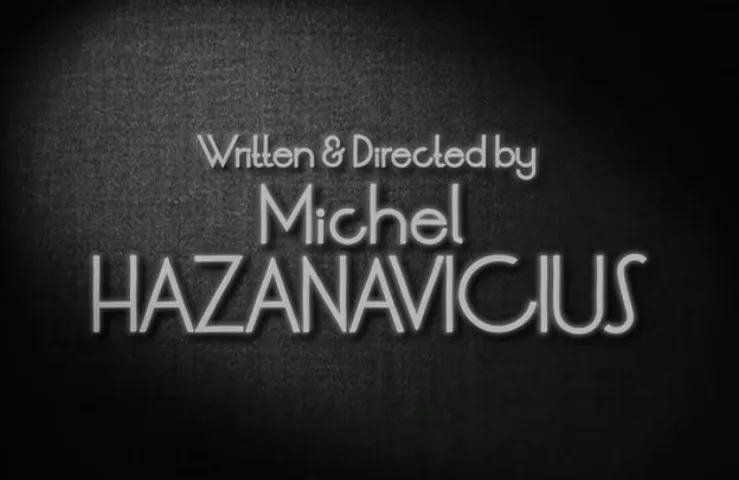

The opening titles are okay, but not great. The font may be custom. I don’t recognize it. Nice quote marks:

I can’t decide if this custom font works or not. It’s not lettering, so that’s wrong, especially since it makes it look more uniform than it should be. It has an appropriately Art Deco feel, but there’s something not quite period about it that I can’t put my finger on. Maybe it’s the little hook on the lowercase “l” or the tilt of the uppercase “C” that feels more 1970s than 1920s to me:

Here is a title from the 1946 film Étoile Sans Lumere, which has a similar style, for comparison:

This may be what they were inspired by, but as you may be able to see, it was hand lettered, and much more charming because of that.

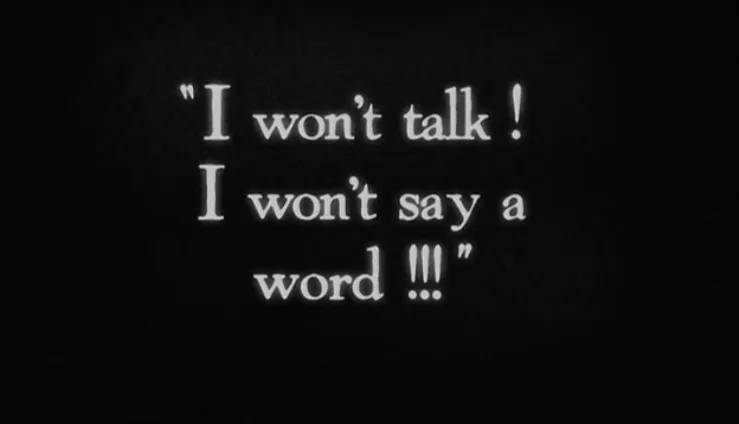

In general, the intertitles—the text used in silent movies to convey dialogue—look right. Two fonts were used. The first is in the movie-within-a-movie near the beginning, a quaint roman face that I wasn’t able to identify. It looks the part, but seems a little too wonky. The right kind of quote marks are used, but they seem to be from a different font:

One small thing here as well: Putting a space before the exclamation point is a French convention. Ironically out of place? Some kind of very subtle foreshadowing? A clue to the nationality of the production designer?

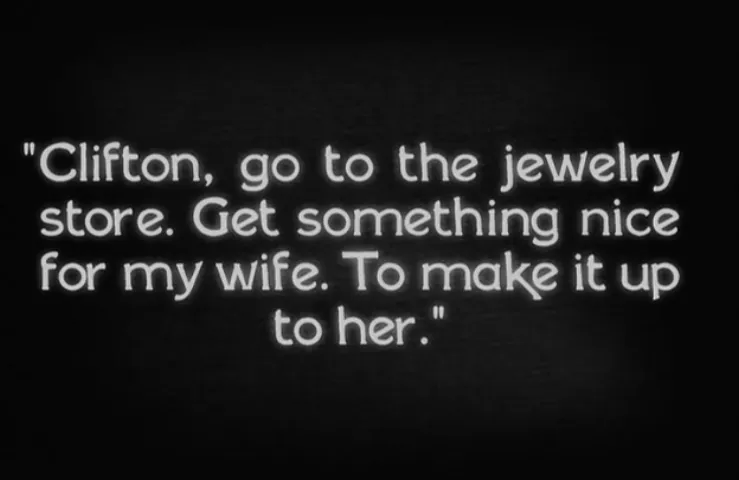

The second face, used throughout the film for (nearly) all the dialog is Silentina, a modern font based on Pastel, a typeface that was actually used a lot in silent movies:

The only problem with these are the “straight quotes.” This kind of quote mark is a hallmark of the digital age. You have to be paying attention to avoid it when setting type on a computer. Silentina’s proper quote marks capture the authentic look:

![]()

…but were not used, unfortunately.

The Kinograph Studios logo shows up a few times. It appears to be set in Hermes with an envelope effect applied to fit the letters into an arch shape. Needless to say, you could not set type this big or distort it like this back in the twenties. Even so, it looks plausible, style-wise:

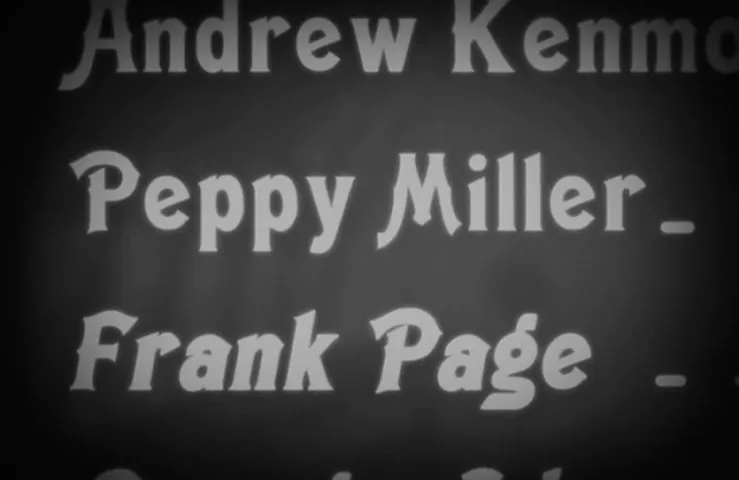

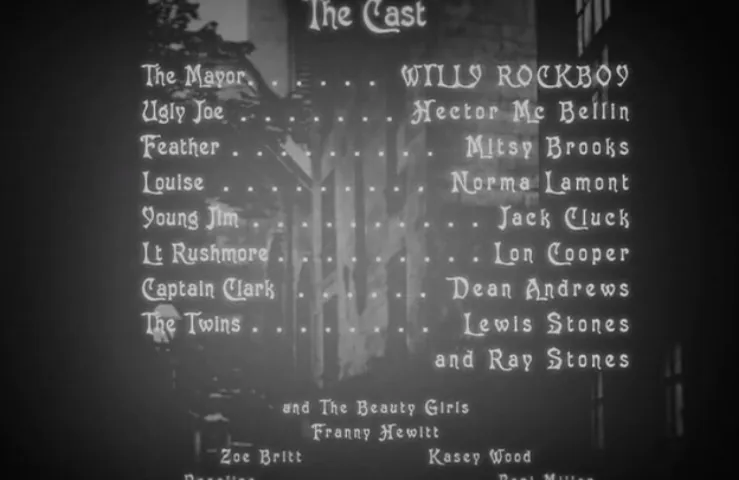

Fonts are used for the title and credit screens in the movies-within-the-movie. The choice of Victorian fonts feels wrong, and these should be hand lettered anyway. So, wrong on two counts:

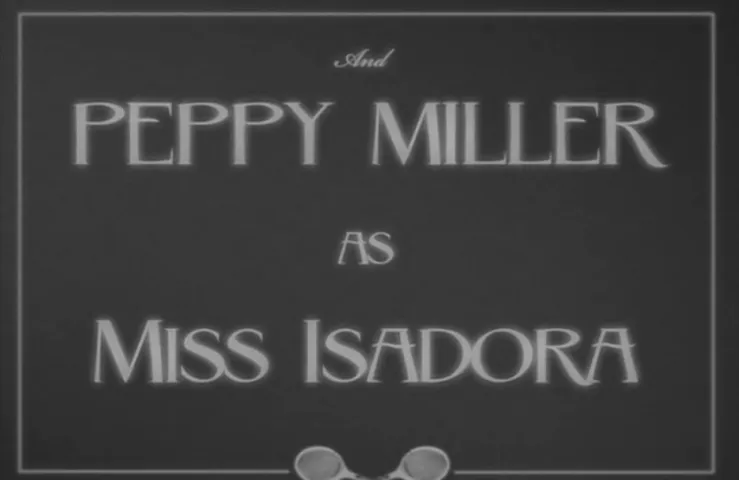

This one is a font, too, but the style looks appropriate for the twenties:

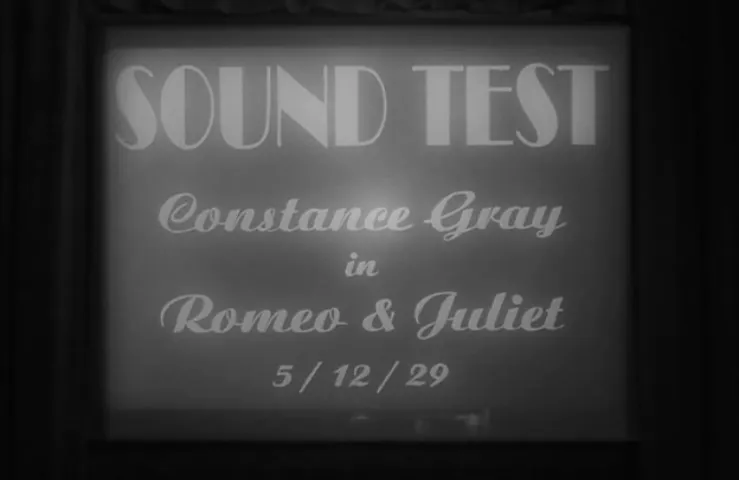

Fonts are used on the slates, too. In this case an old German typeface called Berliner Grotesk. Again, this would have been lettered with a brush, not typeset. You can see it in this one in the small print:

Berliner Grotesk does look a bit like careful hand lettering of the period, but it definitely shouldn’t have been used the way it was in the next one, where the production info should have been handwritten in chalk like the first one:

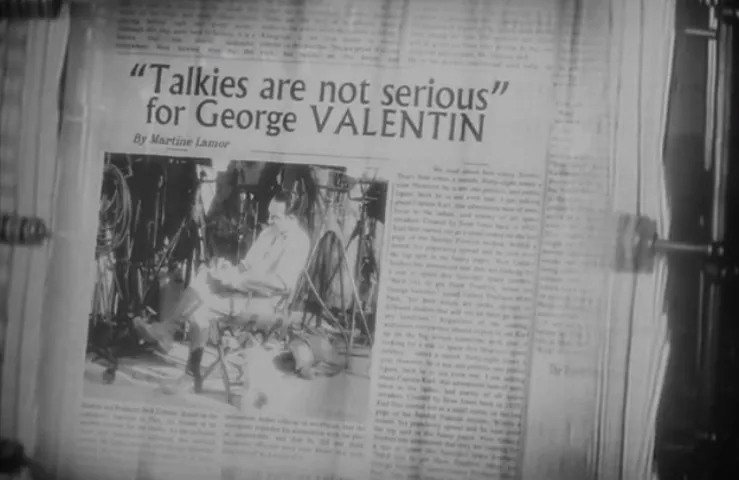

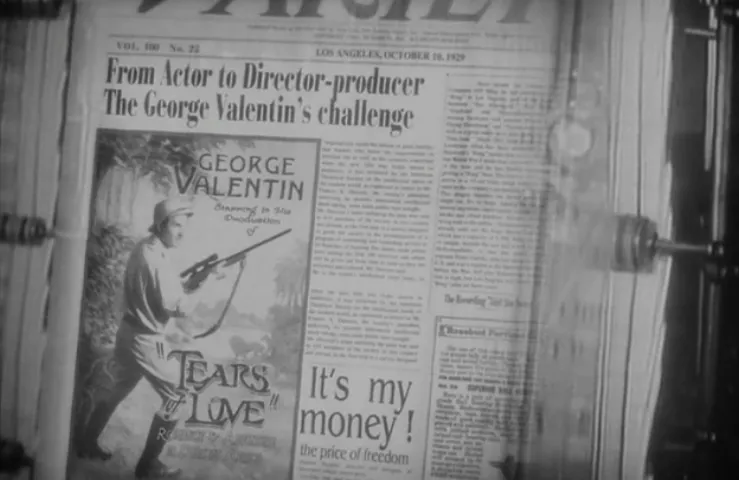

Using fonts in the newspaper props is appropriate, but there are some missteps here as well. The font Albertus, which was released a bit later than when this movie takes place (late thirties), is used several times, but has rarely been used in real newspapers, as far as I know. Not only that, the type is set with negative leading, practically impossible for metal type:

Variety traditionally used either Cheltenham or Franklin Gothic for its headlines. Definitely not this, whatever it is:

And, look, there’s ITC Benguiat (1975):

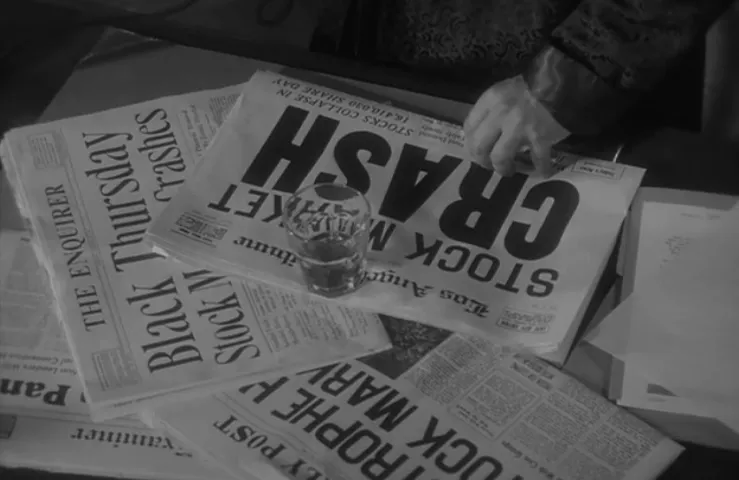

These stock-market crash banner headlines are more like it:

The typography in the magazines and posters is all over the place. I see Goudy Bold (1915), which is okay for the period, but not okay for Variety. I also see some sort of slanted Garamond on the Variety cover, implausible and wrong:

…Plaza (oops—1975), Marker Felt (oops—1992):

…Desdemona (c. 1900—okay), ITC Anna (oops—1991):

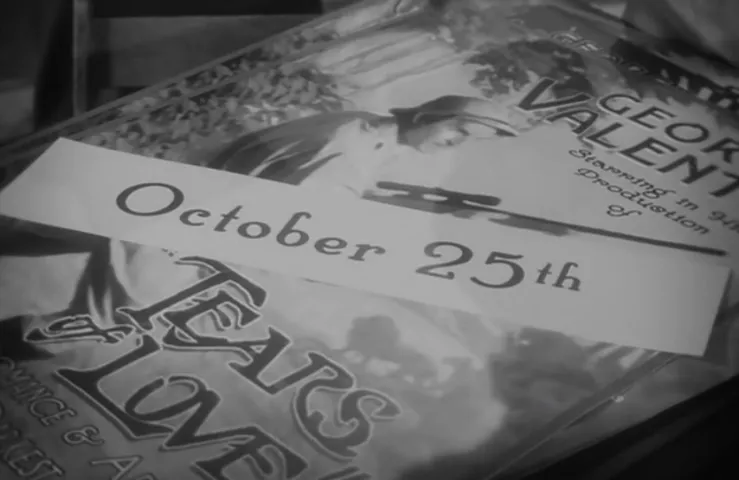

…and a lot of random, probably-recent, ’20s-style fonts I can’t place. Some of these work, as far as it goes. But, again, most of this would not be type, it would be lettering. This poster has the right feel, but the fonts are badly drawn, and “October 25th” would have been some kind of wood type instead of what they used here:

This is probably a font, but a good example of how a font can be used successfully to mimic a hand-painted sign:

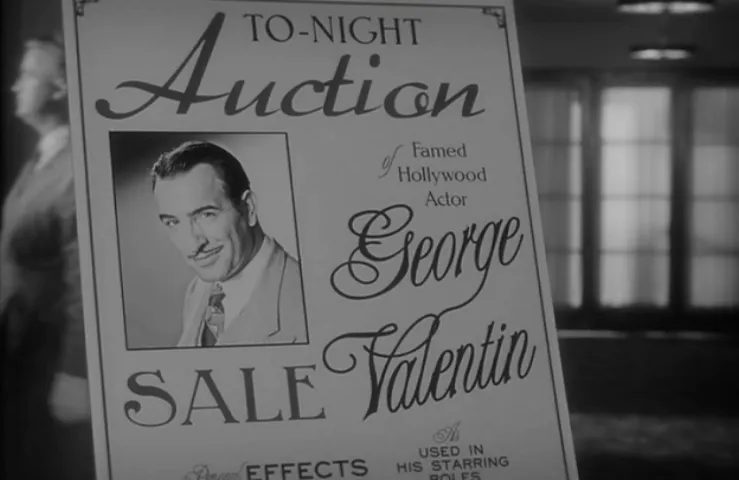

There are some awful fonts in the next example, a classic “show card.” “Auction” is set in a really horrible version of a 1936 typeface called Arabella, and “George Valentin” is set in a poorly digitized version of the 1980s Letraset font Alexei Copperplate:

Next, we see more fonts used, this time for large outdoor signs, which would have been made by sign painters, not typesetters. I’m not going to try to identify all of these, except to point out Futura Extra Bold Condensed and Binner in the first one:

This film leader graphic is perfect, probably from an actual historical film:

But the custom part is clearly fake, and the type is the giveaway—Broadway (1929) and Ariston (1933). Again, it’s not that the typefaces are wrong for the period, but that type would not have been used. Aside from that, both fonts have been distorted to fit, impossible to do with metal type, and a big reason for using lettering on things like this back then:

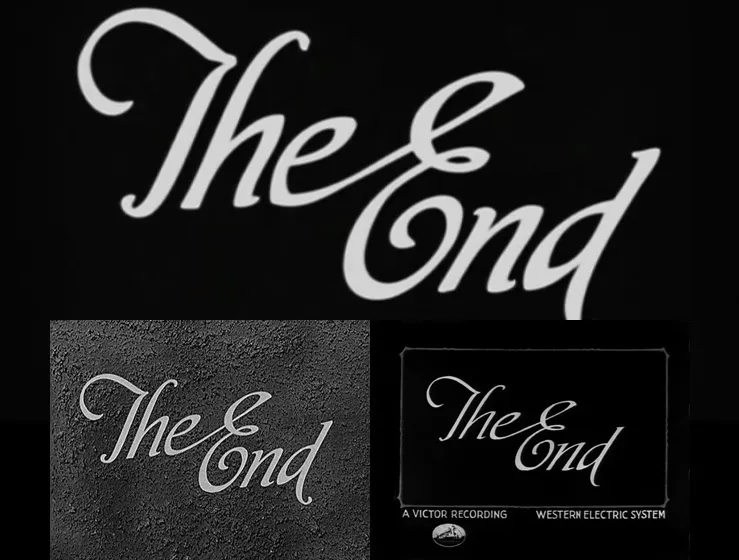

There were two “The End” titles in the movie. Christian Annyas, of The Movie Stills Collection points out that this one is (appropriately) swiped from Laurel & Hardy films from the same era (1927-1930):

The second one is swiped from much later R.K.O. films (1947-1952). It’s not very well traced, either:

In conclusion, the typography in The Artist wasn’t way off the mark—it does seem that some effort was made. And I’m sure that, for 99.999 percent of the movie-going public, it was more than sufficient effort. But it would have been great to see the typography get the same high degree of attention that the other period details in the film got.

Thanks to Christian Annyas, of The Movie Stills Collection for suggesting this article and providing stills.

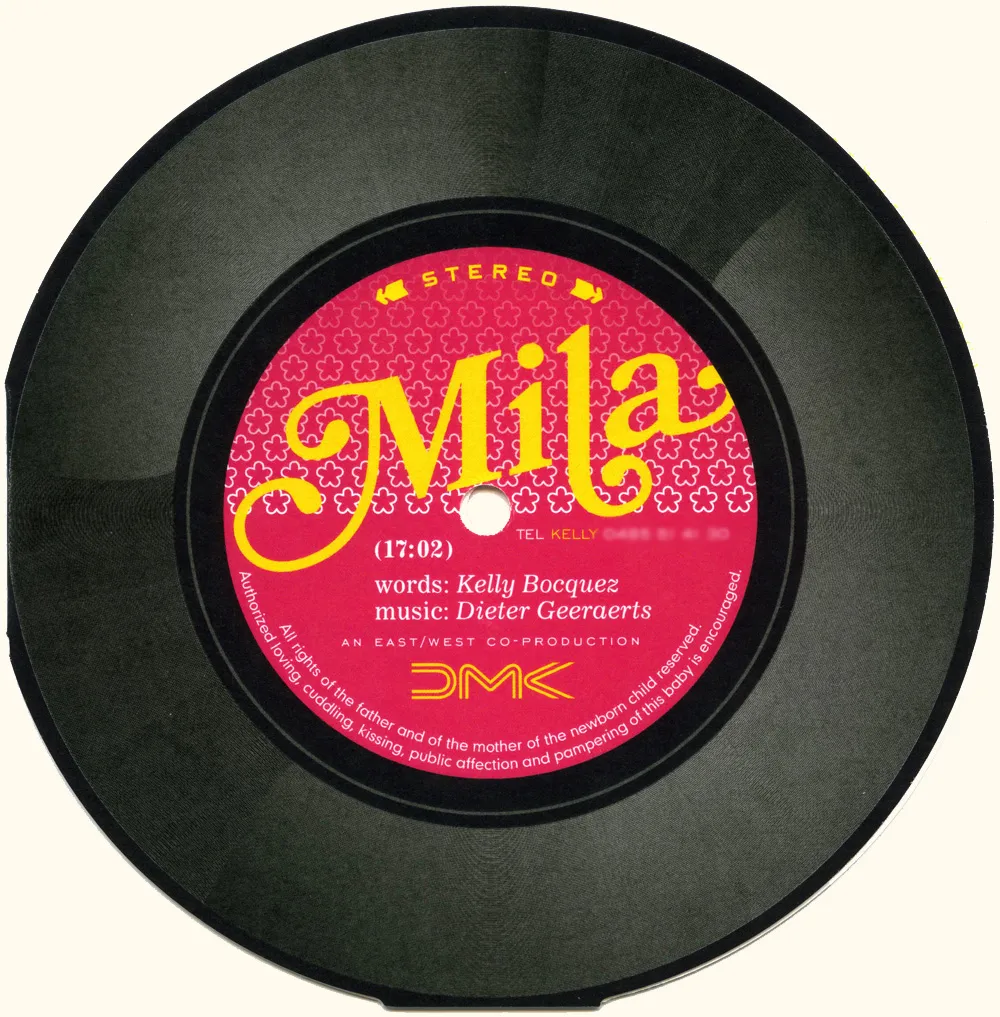

I got this birth announcement in the mail (all the way from Belgium!) that features Bookmania prominently. Designed by Yves Peters (of The FontFeed and elsewhere). Nice!

There’s something Lee Friedlander-esque about this shot I snapped in a parking lot last September in St. Paul. Don’t remember what I was thinking when I shot it.

In yesterday’s installment, I got into the unseemly details of my close encounters with the cast of Mystery Science Theater 3000. This was nothing.

Best Brains, Inc. (BBI), the production company that made Mystery Science Theater 3000 (MST3K), was located in an industrial park in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, a fact that Pat and I confirmed (surreptitiously) one Sunday afternoon in 1991. (I will neither confirm or deny that we peered into the windows.)

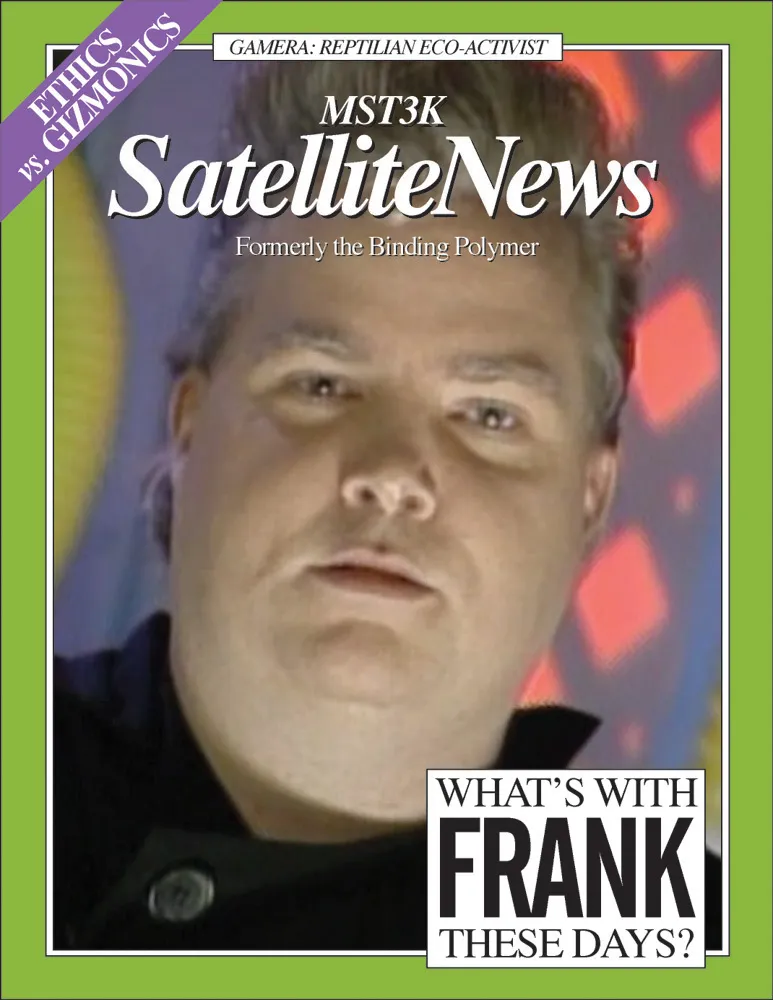

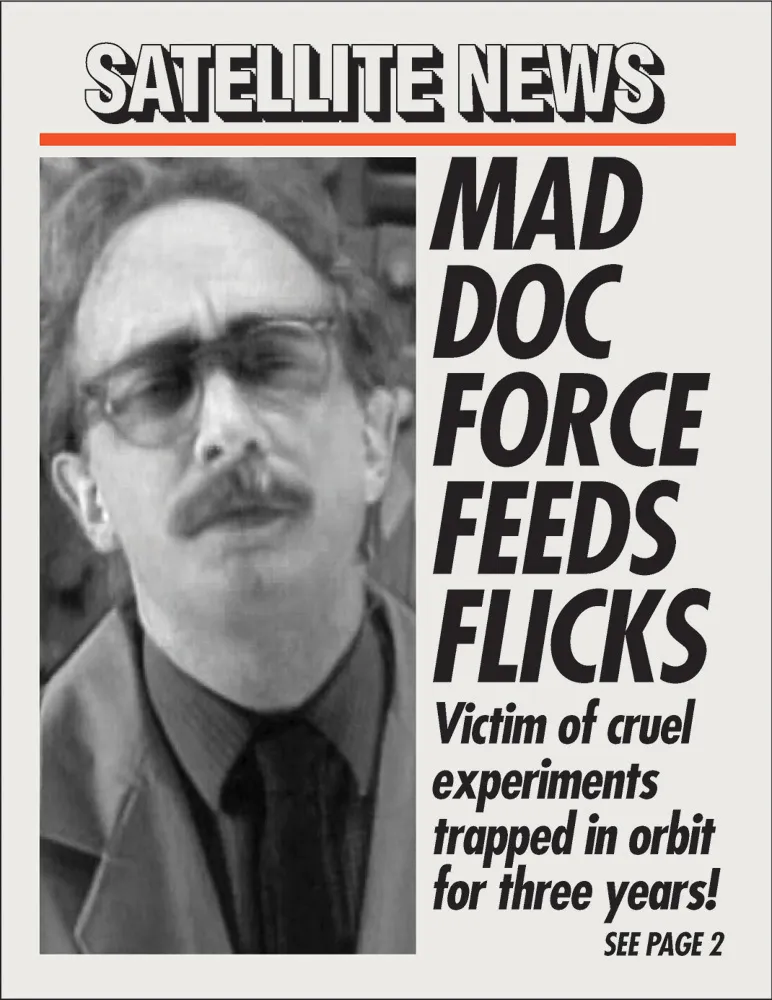

As a graphic designer, I was appalled by the design of the official MST3K fan newsletter, Satellite News (Formerly The Binding Polymer). It was obviously not done by a professional designer. I decided to offer my services—for free, even—to take on design and production of the newsletter. Once they saw what I could do, it would be a slam-dunk. To demonstrate, with the help of a few tapes of the show, an SX-70 camera, an HP ScanJet, Photoshop and Illustrator, and a PostScript laser printer, I did a set of mock “redesigns” of the newsletter. I sent them, along with a cover letter, to Best Brains at the end of October, 1991.

My mock “redesigns” of MST’s fan newsletter, Satellite News (Formerly The Binding Polymer), left to right, top to bottom: The original, as Business Week, as Scientific American, as Popular Science, as Popular Mechanics, as Byte, as Vanity Fair, as Utne Reader, and as The New York Post.

A day or so later, the phone rang. It was Jim Mallon, producer of MST3K! He wasn’t interested in me doing the newsletter, especially for free—that would taking advantage of me. But he loved the “redesigns” and they might have some work for me. He invited me down to the Best Brains offices to talk. I was very excited. Pat was very jealous.

The next day, I showed up at BBI, along with some samples of my work. There must have been some sort of mix up because I had to wait almost an hour. People kept coming up to me to ask if I had an appointment. While I was waiting, I could hear someone editing promo spots for the first of their yearly “Turkey Day” marathons.

At last, Jim Mallon appeared and started off by giving me a tour of the facilities. Along the way, I got to meet most of the people who worked on the show—Frank Conniff, Mike Nelson (who was head writer at the time), Trace Beaulieu, Kevin Murphy, tool master Jeff Maynard (the guy who made the props), Mary Jo Pehl, and Paul Chaplin. Joel Hodgson was out, and I had the impression that he wasn’t often in.

Among the things I saw on the tour:

- The writing room, which had big comfy couches and chairs, a small table with a Mac SE for transcribing ad libs, and a big-screen TV (not very big by modern standards, though).

- Writers’ offices—I remember Trace had the puppets from the KTMA incarnation of the show in his.

- The workshop, where all the props and stuff were made. Among the things I saw in the workshop was the big “Mystery Science Theater 3000” planet seen in the opening credits, which is about three feet tall, and was originally a prop from the Guthrie Theater, repurposed with a bit of hot glue and styrofoam. Also, multiple “trick” Tom Servo and Crow T. Robot puppets made for special effects, like when they needed Tom Servo’s head to blow up or something.

- The main production studio, a large warehouse-like room with the Satellite of Love “command deck” set on one end, and the “Deep 13” set off to one side. The “theater” area was opposite the S.O.L. set and consisted of the theater seat silhouettes (big cut-outs made of plywood) set in front of a large “green screen”. The performers would actually be watching the movie on a small TV monitor out of sight from the home audience. The S.O.L. set was actually raised up about three feet to make room for the performers who worked with puppets.

After the tour, I met with Jim, Trace, and Kevin, showing them some of my work. It seemed to go okay. They told me they were working on some tapes to sell to fans, the first of which was a collection of musical skits from the show called, “Play MST for Me.” I was suddenly in some sort of brainstorming session, and they kept looking at me, maybe hoping for me to be as funny as them. I felt a little ambushed. They were the funny guys. I was a designer. Given the situation, I saw myself (potentially) as what Michael Gross was to the National Lampoon. He never claimed to be a “funny” guy, but he knew how to use design to serve “funny”. In any case, I agreed to come up with some concepts, and I left feeling like I was starting a new page in my career.

When I got home, Kevin Murphy faxed me the copy for the package and I earnestly went to work, arriving at my first concept: Fairly straightforward type with a very long “funny” disclaimer, which I wrote. I faxed it over and waited. This didn’t go over very well—they weren’t expecting me to write copy. I considered what I wrote to be “dummy” text—that they would rewrite it. That didn’t matter, they didn’t like it.

I did a second concept: A parody of a cheesy, sentimental, as-seen-on-TV kind of shlocky record album cover—complete with swash headline type for the title. They didn’t like this one either. It was a design joke and I guess they didn’t get it.

I did a third concept: A record on a turntable, seen from above, with the letters of the title flying off the disc as it spins, a sort of slapstick approach. This one didn’t seem to grab them either, but I don’t remember why.

At this point, the project seemed to be stalled. I thought the ideas I sent them had potential, and could be developed further, but I wasn’t getting much feedback. It seemed almost as if they expected me to “wow” them with a fully-formed idea. I was expecting more back and forth. After a week went by, I called Jim Mallon to find out what was going on. He seemed surprised that I was calling—basically saying “don’t call us, we’ll call you”, and I never heard from them again.

One theory I have is that Trace Beaulieu had been doing all the “design” work, liked doing it, and wasn’t really interested in having anyone else do it. Or maybe they just didn’t like what I did. Or maybe I should have been more proactive, educating them about how to work with a designer. Who knows.

The important thing is, I got a personal tour of Best Brains. I think Pat is still jealous about that.

I don’t have any more MST3K stories to share, but I thought it would be fun to do “remastered” versions of my mock “redesign” covers that I sent to Best Brains. Without too much trouble (yeah, right), I was able to find all but one of the freeze-frames I shot with my Polaroid camera back in 1991 on the DVD collections of the show. (Yes, I have most of them. Are you surprised?) I had to work with my original Polaroid for the “Byte” cover. As a final touch, I added typical color schemes for each magazine. Maybe things would have turned out differently if they’d seen these in color…

Nah.

For those of you who could care less about Mystery Science Whatever It Is, and wish I would post more design-related things, I apologize. Back to regular programming tomorrow.

My mock “redesigns” of MST’s fan newsletter, Satellite News (Formerly The Binding Polymer), left to right, top to bottom: The original, as Business Week, as Scientific American, as Popular Science, as Popular Mechanics, as Byte, as Vanity Fair, as Utne Reader, and as The New York Post.